The Icelandic horse: introduction to the Viking horses

During our winter road trip in Iceland, we were lucky enough to meet one of Iceland’s most emblematic animals, the famous Icelandic horse!

If you’re not yet familiar with this animal and are planning a trip to Iceland, then you’ll definitely want to incorporate some time spent with Icelandic horses into your program. If you’re a rider, or even an occasional horse rider, then it’s possible to enjoy a short Icelandic horse riding, or even a horse trek in Iceland lasting from a few hours to several days.

Icelandic horses are a true breed of horse. There are even Icelandic horse federations in many countries, including France, Germany and the Netherlands. In the USA, there is an Icelandic Horse Congress whose aim is to support the breed and maintain a registry of purebred Icelandic horses in the USA.

The Icelandic horse is a small horse (between 300 kg and 400 kg) with a wide variety of colors. In Icelandic, there are over a hundred different words to describe the colors of Icelandic horses. This breed is very hardy and can make do with a poor diet. Its digestive system assimilates many more nutrients than horses of other breeds. This can be a problem when an Icelandic horse lives in a country where grass is rich and readily available.

We spent a lot of time observing and photographing horses in Iceland. Seeing them live in this wilderness, sometimes in stormy weather, was a pure joy that we share with you in this article.

The Icelandic horse: a Viking horse!

When the Vikings colonized Iceland, arriving shortly before the year 1000, they not only needed draft horses, but also animals to get around in a hostile environment. They brought horses from Norway, particularly from the fjords, to the island.

Subsequent waves of Scottish and Irish immigration enriched the heritage of these horses with Celtic breeds similar to Connemara, Highland and Shetland ponies.

It would also appear that the genetic heritage of Icelandic horses contains genes from Yakut ponies and Mongolian horses.

In short, the genetic basis of Icelandic horses is a condensation of hardy horses living in arctic or extreme climates. Iceland then forged these Nordic horses, and within a few generations, the Icelandic horse breed was born!

Laws protecting Icelandic horses

Less than a century and a half after Iceland’s colonization, the Althing, Iceland’s parliament of the time (and the first in Europe), banned the importation of horses into Iceland. This law also applied to individuals born on the island. Buying an Icelandic horse and transporting it to another country is like banishing it from its native land for life. So think carefully before adopting an Icelandic horse.

The aim was to protect Icelandic horses following crossbreeding attempts that led to degeneration. This ban is still in force today, over 1000 years later.

In fact, the Icelandic horse lived in a bubble, protected from cross-breeding, disease and parasites that could have been imported. Natural selection then took place, and over the centuries the elements forged the Icelandic horses as we know them today.

We call it an Icelandic horse, not an Icelandic pony!

If there’s one thing that offends Icelanders, it’s being called an Icelandic pony instead of an Icelandic horse. Indeed, despite their small size, these animals are not ponies. There are many reasons for this, including their temperament (a pony is calm, an Icelandic horse is fiery!), their heavy weight, their bone structure, which is closer to a horse than a pony, and so on.

Icelanders consider these animals to be horses, and always have. And this is true no matter what their size (some individuals measure no more than 115cm).

So if you don’t want to offend Icelanders, be sure to strike “Icelandic pony” from your vocabulary!

The tölt, a gait unique to Icelandic horses

Free-roaming horses have four different gaits: walk, trot, gallop and back up. These four gaits are present in all horses, regardless of breed.

But the Icelandic horse has an additional gait that is much appreciated by riders: the Tölt!

The Icelandic horse’s tölt is a four-beat walking gait. Icelandic horses that tölt keep one hoof on the ground at all times. This gait is more stable, but also more explosive. It’s also genetic, meaning that horses don’t need to learn it – it’s innate.

Riders from all over the world appreciate Icelandic riding for the comfort it provides. This is particularly true of horseback riding in Iceland, where the terrain is rugged. The tölt makes it possible to ride through these hostile territories without being jolted like a gallop.

However, while all Icelandic horses tölt, some individuals prefer to trot or gallop. We don’t really know why this variation occurs, but scientists are beginning to isolate certain genes associated with tölt. This breakthrough could help explain why some horses are (naturally) more inclined to tölt.

Wild Icelandic horses?

We’ve heard a lot about Icelandic wild horses. Many people think that the Icelandic horse is a wild horse that lives on the tundra. But the reality is a little different. In Iceland, there are no ownerless horses. These owners are responsible for their animals and their well-being.

However, in some parts of the country, there are horses living in the wild all year round. For example, we observed a group of Icelandic horses in the Westfjords, living on an isolated peninsula with no human contact, even in winter.

Although the Icelandic horse is not wild, it remains a hardy species capable of living in the most extreme conditions. Their life expectancy is much higher than that of other breeds. Some Icelandic horses have lived very long. One Icelandic mare set a record of 56 years.

Icelandic horse colours

The variety of colours on Icelandic horses is quite incredible. There are over 40 different colours. Each individual looks unique. The most common Icelandic horse colours are chestnut, brown and bay.

Icelandic horses’ colours vary from season to season and with age. They are often born with a colour that changes with age.

Some Icelandic horse colours are very old. For example, genetic studies have shown that the Sabino colour appeared more than 2,500 years ago in Siberian horses.

Researchers believe that the gene responsible for the grey color in horses probably comes from an adaptation to a marshy environment like the horses of Camargue. This colour enables them to camouflage themselves better in the water, which reflects the grey clouds.

In addition to this great diversity of Icelandic horse colors, there are also individuals that have characteristics specific to other breeds. This is notably the case with the mullet stripe (found in the Norwegian fjord) or the leg bars (or zebra bars) of certain Icelandic horses. These stripes are more a feature of primitive, wild horses.

Finally, the appearance of Icelandic horses is completely different in winter and summer. When the cold sets in, the horses develop a second layer of thick, dense hair. This extra insulation enables them to withstand the extreme conditions of the Icelandic winter. They look like real fur balls!

When May arrives, they lose their winter coat and look finer.

Horseback riding in Iceland

It’s possible to go horseback riding in Iceland. Riding a horse across the tundra, in summer or winter, is a must for all riders travelling to Iceland.

It’s important to remember, however, that Icelandic horses, like all animals with freedom of movement in the wild, are not always predictable. They will certainly want some food if you have some with you, but it is better not to feed them, so as not to cause them health problems.

Similarly, keep your distance so as not to surprise them with a sudden move.

Finally, if you decide to go horse riding in Iceland, be sure to visit a specialist farm. Don’t try to ride them yourself (even if you’re an experienced rider!) and follow the owners’ recommendations.

Finding a horse ride in Iceland is not very complicated. It all depends on your itinerary. The starting point is to choose a region and find an riding school or farm close to where you are going.

Our preference is North Iceland for horse riding. The reason for this choice is simple: there isn’t a living soul for dozens of kilometres and the northern landscapes are magnificent. During our trip to Iceland in winter, this is where we most enjoyed watching Icelandic horses. Let’s take a tour of Iceland by region to explain the differences. We’ll also give you some recommendations for finding the equestrian centre that will offer you the Icelandic horseback ride of your dreams.

Horse riding in the north of Iceland

If you love snow, ice and mountains, then we recommend that you go horse riding in the north of Iceland. Many farms, such as Stable Stop Farm in Ytri-Bægisá (20 minutes from Akureyri), offer short rides on Icelandic horses and horse treks.

In winter, it snows more than elsewhere in the region. The scenery is breathtaking. White mountains, partly frozen rivers, big flakes caressing your cheek – the perfect backdrop for anyone who loves winter.

A little further north, near Husavik, the family-run company Lava Horses offers a few hours of Icelandic horse riding for novices, and a day-long Icelandic horse trek for the more experienced. The setting is equally magnificent. Did we mention that Húsavík is our favourite fishing village?

Icelandic horse riding near Reykjavik

A number of Icelandic farms offer horse riding tours departing from Reykjavik. But some, like IsHestar, are right on Reykjavik’s doorstep. In just 20 minutes from the centre of Reykjavik, you can be in the Icelandic countryside on horseback. This is the best way to enjoy Icelandic horse riding if you’re only coming for a few days.

Laxnes Horse Farm is also very close to the capital, half an hour north-east of Reykjavik. Most of the horse riding farms near Reykjavik offer a minibus service to pick you up from your hotel and take you to the starting point of the ride. Of course, this bus transfer costs money, so if you have a car, you might as well go by car.

However, it’s not possible to go horseback riding in Reykjavik itself, as horses, like tractors, are banned in the capital.

Icelandic horseback riding in Vik

Vík or Vík í Mýrdal is a village in the south of Iceland. It is best known for its black sand beaches, its trolls frozen in the ocean and its church, which towers over the village and the North Atlantic.

But what is also becoming increasingly popular is to go for an Icelandic horse riding tour on Vík’s black sand beach. The company Vik Horse Adventure offers short horseback rides departing from the village. This horse ride is certainly the most spectacular in the country, such is the uniqueness of the landscape around Vík. Many film and TV scenes have been shot here. In the TV show Vikings, for example, Floki arrives in Iceland on this beach.

If you go to Vík in summer, you can take the opportunity to walk around the cliffs of Dyrholaey and watch the puffins, of which there are many in the area. Birdwatching in Iceland is also one of our favourite activities.

A short video about Icelandic horses made by Samy

The Icelandic horse in Norse mythology

The Vikings have always worshipped horses. For them, horses were animals that allowed the gods to travel from one kingdom to another. But we’re talking about a pagan religion where the rituals were violent. For example, during the Blót, ceremonies practised in the Germanic pagan religion, horses were sacrificed and eaten. When the Vikings arrived in Iceland, they still practised these rituals, which survived Christianisation for several centuries. Icelanders are heirs to this culture.

The Icelandic horse is also mentioned in the Landnámabók (the book of colonisation). It says, for example, that Skalm, the Icelandic mare of the Seal-Thorir clan chief, sat down one day to rest. The chief then decided to found a colony there. However, the story does not say where this place was.

Popular Icelandic sagas such as the Saga of Njáll the Burnt and the Saga of Grettis mention the Icelandic horse.

Today, Icelandic horses continue to be named after horses from Norse mythology or Icelandic Sagas. Just as Icelandic men and women (humans this time) still bear the names that were used during the Viking era and long before.

During the Icelandic Middle Ages and periods of conflict, wars were commonplace. Horses were essential animals. They were revered by warriors and many were buried with their mounts, as was the practice during the Viking era.

Finally, in a somewhat barbaric but true story, the Icelanders used to organise Icelandic stallion fights for entertainment and to select the best stallions for breeding. These fights took on unimaginable proportions when their owners got involved. The matter could become serious and political.

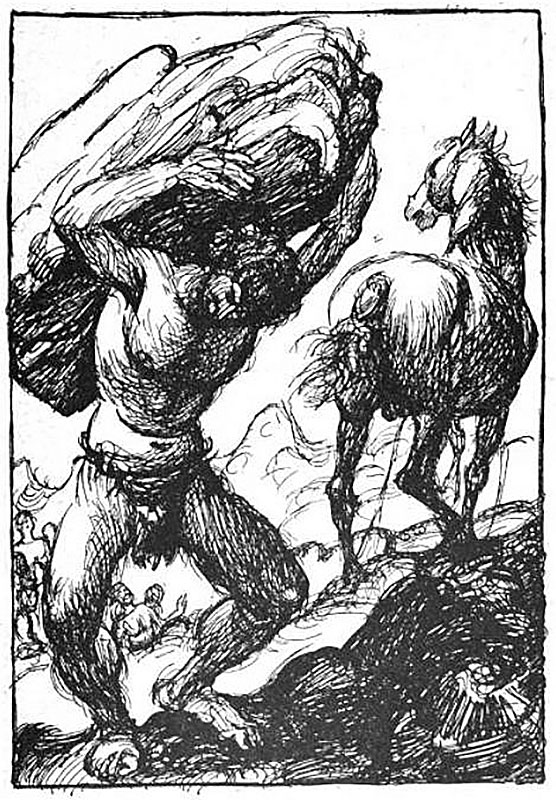

Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse of the Norse god Odin

Odin is the most important god in Germanic mythology. He is the father of everyone, including the other Germanic gods Thor and Baldr.

The god Odin had an eight-legged horse named Sleipnir. This horse, was considered the best of all horses. He could even ride as far as Hel, the realm of the dead in Norse mythology.

And of course, in Iceland, Sleipnir was an Icelandic horse! The breed is a worthy representative of the power and wisdom of Odin’s horse. In fact, the natural site of Ásbyrgi in northern Iceland, a canyon in the shape of a horseshoe, was considered to be proof of Sleipnir’s passage through Iceland.

Legend has it that it was Odin’s horse that placed a hoof on the ground there, forming this huge horseshoe-shaped canyon. The site is nicknamed “Sleipnir’s footprint”. Just imagine the size of Sleipnir!

Finally, Ásbyrgi is a great place for a little nature and history walk. It’s located around sixty kilometres east of Húsavík. A campsite and information centre are available nearby.

Sleipnir is depicted in numerous Germanic sculptures and frescoes. For example, the Tjängvide image stone is decorated with several figures, including the horse Sleipnir and the god Odin riding towards Valhalla. This stone is one of the highlights of The Swedish History Museum.

The other horses of the Norse gods

In addition to Sleipnir, many other horses are associated with the gods in Norse mythology. These beliefs and legends are best known from Snorri’s Edda and the Poetic Edda (Codex Regius). These two documents, written in Iceland by Snorri Sturluson and Sæmundr Sigfússon, are of fundamental importance to Germanic culture.

For example, there is Blóðughófi, or bloody hoof. This horse belongs to the god Freyr and is capable of crossing fiery darkness. In the Poetic Edda, the god Freyr gives his messenger Skírnir the horse Blóðughófi to meet Gerðr, a giantess living in Jötunheimr.

Árvakr and Alsviðr, the horses that pull the sun chariot

Two other horses are very popular in Norse mythology: Árvakr and Alsviðr. These two horses, associated with the sun goddess Sól, are responsible for pulling the sun chariot. Pursued by the wolf Sköll, whose aim is to destroy the sun, they must constantly run to escape him and keep the day alive for humans and animals. In fact, when the wolf Sköll manages to catch up with the two horses and the goddess Sól, it causes a solar eclipse. The eclipse ends when the goddess escapes the wolf again.

Árvakr’s ears have also been branded by the god Odin himself. As for Alsviðr, Odin has engraved its hooves with Runes.

Finally, on the Ragnarök, the end of the world according to Norse mythology, the wolf Sköll catches up with Árvakr, Alsviðr and the goddess Sól, and devours the sun, extinguishing it forever. This is how the world becomes dark.

Svaðilfari and the fortress of Ásgard

Legend has it that the giant builder (who had no other name than this in Norse mythology) made a bet with the gods to build the fortress of Ásgard in half a year. This giant had a horse named Svaðilfari. His horse was endowed with magical powers and incredible strength. The two of them set to work and almost succeeded in completing the project on time.

When the gods saw that the builder and his horse Svaðilfari (or Svadilfari) had succeeded, they decided to send the god Loki to derail the work. Loki transformed himself into a mare to distract Svaðilfari. In fact, it was from their union that Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse of the god Odin, was born.

The builder and his horse Svaðilfari failed in their project and Sleipnir was born of this adventure.

Many other horses are mentioned in Germanic mythology. The horse is certainly the most common Nordic animal. And the Icelandic horse is the heir to this culture.

The end of sacrificial rituals

In Norse mythology, the horse was associated with the gods and war heroes. They carried men and women to Valhalla. They pulled the chariot of the moon and the sun, making day and night. Horses were of paramount importance and played a central role in Scandinavian life.

Stallions were associated with fertility. They were therefore at the centre of religious sacrificial rituals. Their bones were used in many ways. The Icelandic sagas even mention their use in black magic.

During the Christianisation of Scandinavia and Iceland, shortly after the Viking era, these horse-related practices, particularly the consumption of horse meat, were demonised and condemned. But while the rituals gradually disappeared, people continued to eat Icelandic horsemeat on an occasional basis.

Today, a minority of Icelanders eat horsemeat.

Numerous archaeological finds in Iceland have shown that horsemen were often buried with their Icelandic horse. Sometimes, saddles and bridles were even found in the graves, proof that Icelanders believed, even after Christianisation, that their Icelandic horse would carry them to Valhalla.

Where to see horses in Iceland?

Horses can be seen just about everywhere in Iceland. But there are more of them in some places than in others. For example, in Isafjordur and the Westfjords, there are very few horses. You really have to know the Westfjords to find them.

We would say that we saw more Icelandic horses in the north and north-east of the country than elsewhere on the island. It’s fairly easy to see horses around Akureyri, the country’s second largest city after Reykjavik. Between Akureyri and Egilsstaðir in the east, there are plenty of horses, not to be confused with the wild reindeer that roam in groups here and there as you approach Egilsstaðir.

If you’re travelling around the island, there’s no need to ask where to see horses in Iceland – you’re bound to see them everywhere. If, however, you do want to focus, then we recommend three areas:

- Around Akureyri to the north and as far as Húsavík.

- Around Egilsstaðir in the east.

- Around Selfoss in the south-west (closest to Reykjavik).

- At Vík í Mýrdal, in the south.

- All over the Snæfellsnes peninsula in the west.

- In the Golden Circle region.

In winter, Icelandic horses stay close to their homes, as there’s nothing to eat in the mountains. This makes it easier to see them. Be careful, however, not to enter private property to see them, as the owners can sometimes be virulent.

Our experience with the Icelandic horse

We had some wonderful experiences with Icelandic horses, simply by observing them. Seeing them evolve in their natural environment, facing the most extreme elements, was incredibly beautiful. They always seem unflappable, even in the face of a blizzard. Their calm contrasts with their strength. Sometimes they are gentle, sometimes they seem ready to lift mountains.

After a storm, their hair are covered in ice, and they seem to have stepped straight out of a mythological tale. They then dig through the snow to find the grass they need to survive.

It has to be said that Icelandic horses are not kind to each other. Hierarchy seems to be important. In fact, it’s quite impressive to see an Icelandic stallion commanding the respect of the others!

As for the young horses, they spend their time quarrelling and playing, like many other mammals. It is at this point that the hierarchy is established and the dominant ones impose themselves.

They spend their time feeding and socialising, waiting for the next storm. Their social behaviour is very different at this point: they band together and show solidarity! Icelandic horses support each other in their diversity!

Finally, we spent a lot of time photographing Icelandic horses. We were attracted by the poetry that emanates from these animals. What a privilege to witness these delicate and fleeting moments, but also to immortalise them with a camera. We wanted to share the beauty of what we saw.

Photographing Icelandic horses: our advice

Whether you’re an amateur photographer or simply want to immortalise your adventures in Iceland, there are a few rules to follow when photographing horses in Iceland. On the one hand, you must look after the welfare of these animals. Secondly, it’s not always easy to photograph animals. Here are our 8 tips for photographing horses in Iceland:

- Always keep a safe distance between yourself and Icelandic horses. This distance is necessary for their well-being and your safety. This rule is even more important if you are unable to recognise an Icelandic stallion.

- Give preference to horses you come across in the mountains, far from farms. This will help you avoid misadventures with the farmers.

- Choose your background carefully. For example, photos of Icelandic horses in the snow-capped mountains are more interesting than in the plains, where the background can be banal.

- Be patient, photographing Icelandic horses can take time, as they move around a lot.

- In summer, wait for the evening light. Photographing an Icelandic horse under the midnight sun can be a wonderful experience.

- In winter, you can take advantage of the darkness to take incredible photos of Icelandic horses under the Northern Lights. But you’ll need a tripod to do this.

- Some colors catch the light better than others, so choose your subjects carefully.

- Horses should always be photographed from a slightly lower angle, so as to be at eye level, or even from the bottom to give them more presence.

If you’re an amateur photographer and you’d like to travel to Iceland to do some photography, then don’t hesitate to contact us, we’d be delighted to offer you one of our photography workshops in Iceland.